In Toronto, where I do most of my biking, bike ridership is growing, but a fully-fledged bike culture has yet to emerge. I mean this in as broad a sense as possible. There are certainly cyclists, and bike scenes, and various cycling-subcultures. But cycling has yet to become fully integrated into the fabric of the city. A large percentage of the cyclists on the road are relatively new cyclists, and are fairly inexperienced at cycling amongst others. As such, one of the chief defining factors of a culture, namely, an accepted set of behavioural norms, has yet to be established. Many questions of etiquette present themselves.

Of the many issues of bike etiquette that I debate with my cycling friends, the issue of the pre-emptive pass (henceforth PEP) has been particularly controversial. Most people who bike have experienced this at some point or another: you stop at a red light next to the curb, and another cyclist pulls up next to you on your left, with the clear intent of over-taking you once the light turns green. (As with most facets of biking, this phenomena has been explored by Bike Snob NYC, which he dubs “shoaling” (which is frankly kind of an obscure term to use) to denote the collection of people each attempting to pre-emptively pass the other. I personally rarely see more than one person at a time attempt the PEP, but occasionally I will see two. But three cyclists side by side does not a shoal make).

By pulling up next to someone at a light, you are non-verbally announcing your intention to pass them, implying that you are a faster rider than they are. And therein lies the question of etiquette. It is in many regards, rude. This is undoubtedly the source of many Cat-6 races, as some cyclists view the PEP as a challenge, if not an outright affront (I personally admit to going for the holeshot against someone trying the PEP on me). For these reasons, I used to never attempt a PEP on other cyclists; I would properly line up behind the other cyclists waiting at a light. Once the light changed and the paceline started, if I found the pace was too slow, I would then pass the cyclist(s) in front of me.

One day I chastised a friend for doing a PEP, he made the case that the PEP is a far safer way of passing people. The argument is hard to dismiss. Passing people while moving invariably puts you at risk from moving automobile traffic, and generally forces you to pass them at a closer distance. It’s a more involved procedure. If there are several people you wish to pass, this only increases your risk from cars, as well as increasing the chances of Cat-6ing, as each new person you pass might try to match your speed and disallow the pass. The PEP on the other hand allows you to firmly establish your place in front of (non-moving) automobile traffic and you only have to worry about one Cat-6er, the person at the front of the line.

So, I started doing PEPs a little more often. But as with most questions of social etiquette, performing a pre-emptive pass in an acceptable way requires a sort of tacit judgement (whether something is rude or not is often ambiguous to me). First, you have to have good reason to suspect that you are going to pick a pace faster than the person you are going to PEP. For example, if I’m closing a gap on a cyclist and then we both end up at a red light, that’s a safe bet. If the cyclist is already stopped, I let them set the pace and then pass if necessary. If I’m on my road bike on a training ride, I almost always PEP. So far I’ve avoided Cat-6s and dirty glances. Most commuters seem perfectly happy to allow me to PEP. These are the kinds of unwritten rules that one gleans through experience.

However, I’ve personally seen a number of egregious PEPs. Doofuses on slouchy 26″ MTBs moving to the front of a long line of commuters only to be passed on the inside by all of them. And I have seen horrible Cat-6s emerge. Things get especially dicey when a person tries to PEP another PEPer. These scenarios increase risk, rather than lessen them. And the PEP is just one of many possible examples of such issues. I expect transgressors will multiply as ridership numbers continue to increase.

There are some general ways of creating a friendly, cooperative, safe bike culture. Questions of etiquette tend to revolve around a broad social concern: what would be the consequence if everyone acted in a particular way? Obviously, if everyone was an over-zealous pre-emptive passer, chaos would ensue. So, viewing PEPs as poor cycling etiquette seems to be a fair generalization. There are exceptions to any rule, as the examples I gave above, and those tend to be context dependent. When in doubt, however, revert to the general rule.

But etiquette is also linked to infrastructure in crucial ways. Of the many things that people on bikes do that motorists (and pedestrians) can’t stand, most are chiefly a function of poor infrastructure. Riding the wrong way on a one way street, riding on the sidewalk, passing on the right of cars at lights (another form of pre-emptive passing), “taking up a whole lane” – all of these can be addressed by improved infrastructure for people on bikes.

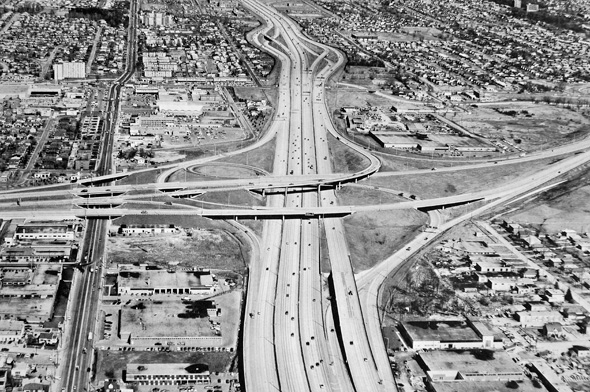

Likewise for pre-emptive passing. If bike lanes are wide enough to allow for two lanes of bike traffic, then the issue of the PEP becomes diminished. Passing in general is facilitated, so there is less of an urge to pass pre-emptively, and two lanes of traffic based on pace are established, making it less likely that a cyclist will be stuck behind one riding more slowly. In Copenhagen (check the pic), for example, I never observed any of these issues. No Cat-6ing, no pre-emptive passing. And this is a result of ample cycling infrastructure. There’s more room for people to bike, so cyclists are not constantly struggling against one another.

So, while questions of etiquette superficially seem to involve interpersonal acts – acting nicely or rudely towards another person, our built environments can encourage or discourage certain behaviours. We quite literally build our etiquette – our social values – into our infrastructure. So, the solution, as usual, is to build more and better bike lanes!